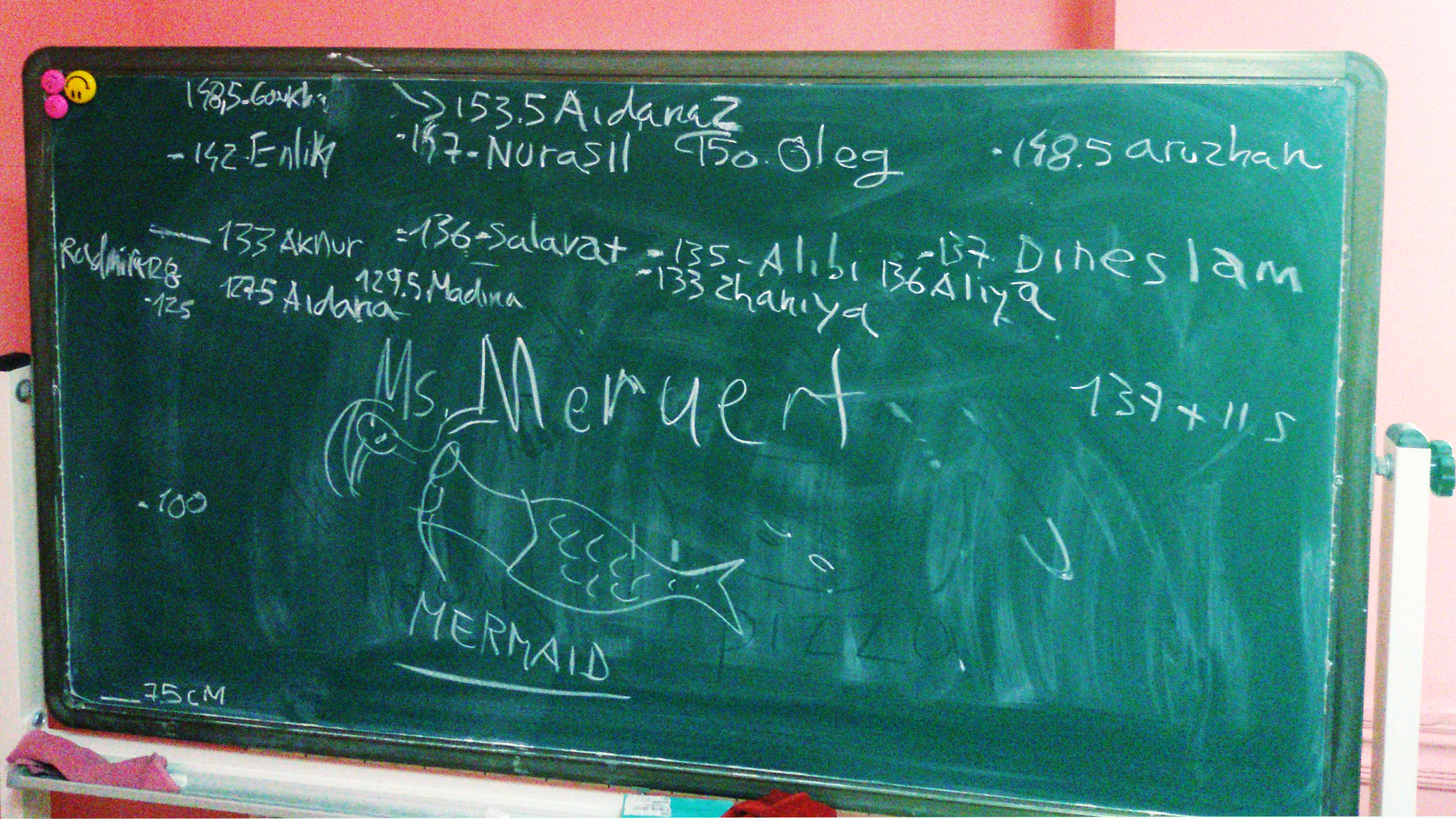

In the school where I work now there aren't any projectors, there is one laptop for all the teachers, there are basically no textbooks, the rooms are rather small and often the teacher has to use blackboard and chalk because there are no markers to be used on the whiteboard (the whiteboard doubles as blackboard on the flip side); often, for at least half of the month, Internet doesn't work and many days the electricity comes and goes. There is no staff room either and teachers are expected to sit next to the only printer to do their printing, in a busy passage between the reception and the stairs (there are no copiers, only this one very inefficient multi functional printer which is mostly used as copier, and I'm only waiting for the time, very soon, when it will collapse under the work load).

In this context, I suddenly developed a keen interest for everything Dogme, since my lessons, whether I like it or not, have to follow most of its principles, namely:

Resources should be provided by the students or whatever you come across. If doing a lesson on books then go to the library.

All listening material should be student produced.

The teacher should always put himself at the level of the students.

All language used should be 'real' language and so have a communicative purpose.

Grammar work should arise naturally during the lesson and should not be the driving force behind it.

Students should not be placed into different level groups.

To this, I should add that most of the hours I teach are focused on preparing teenagers for exams, something which, on one side, makes everything more difficult, since I am expected to input some exam material which needs to be printed and does not really have a relevant interest for the student, thus breaking one or two of the Dogme principles -- but on the other perfectly abides by its rules because it places the direct study of grammar out of the classroom.

All considered, I am quite intrigued by Dogme right now. Long ago I made mine the principle that the teacher does not blame a bad lesson on the equipment -- and I stick by it. I just make do, like all the other teachers here, locals who don't even expect things to be different (though they seem to strangely manage by enforcing a "traditional" school discipline i.e. students stand up when the teacher enters and teachers are addressed as "mister" and "miss", something that to their bafflement I refuse to comply with).

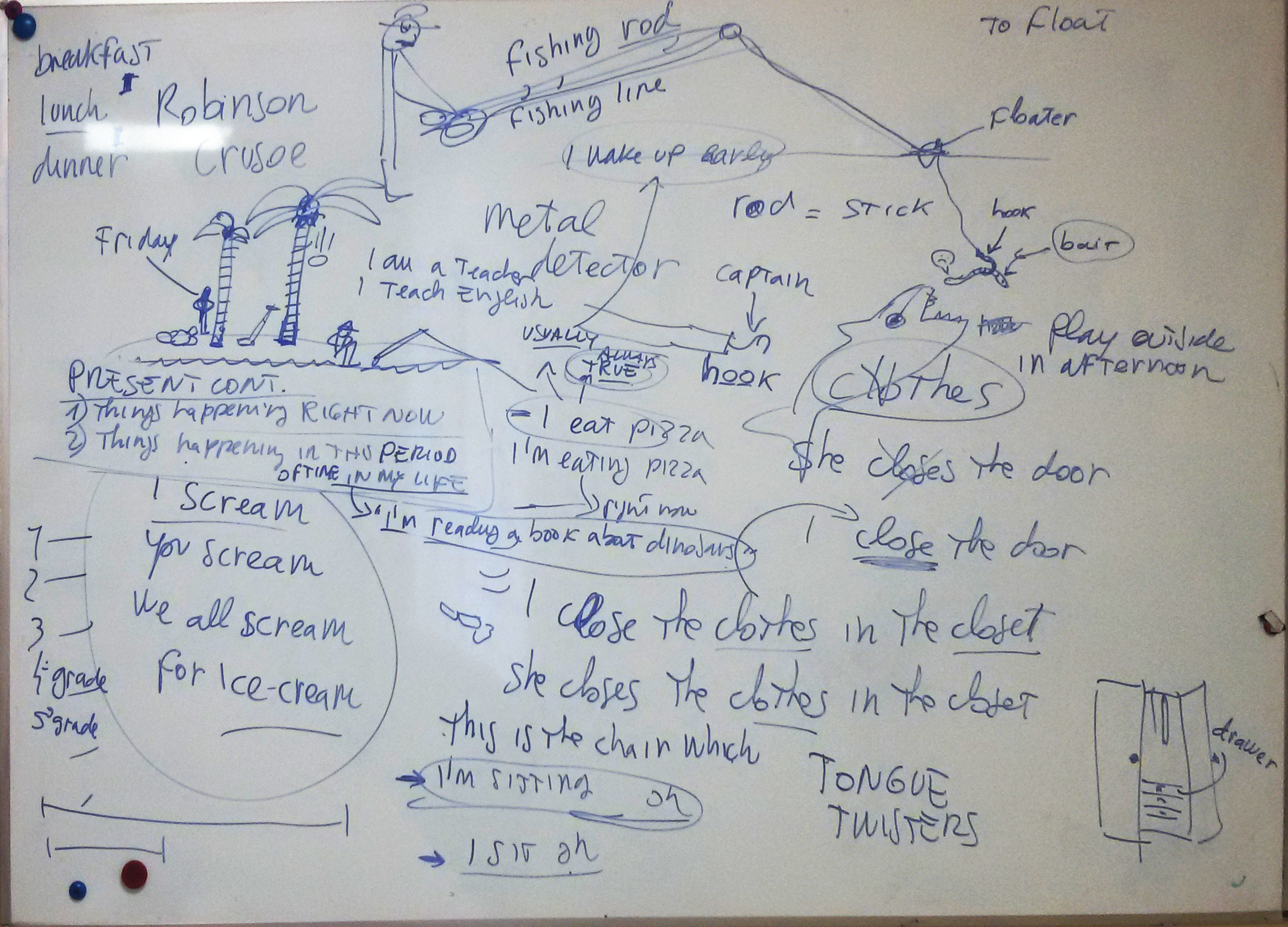

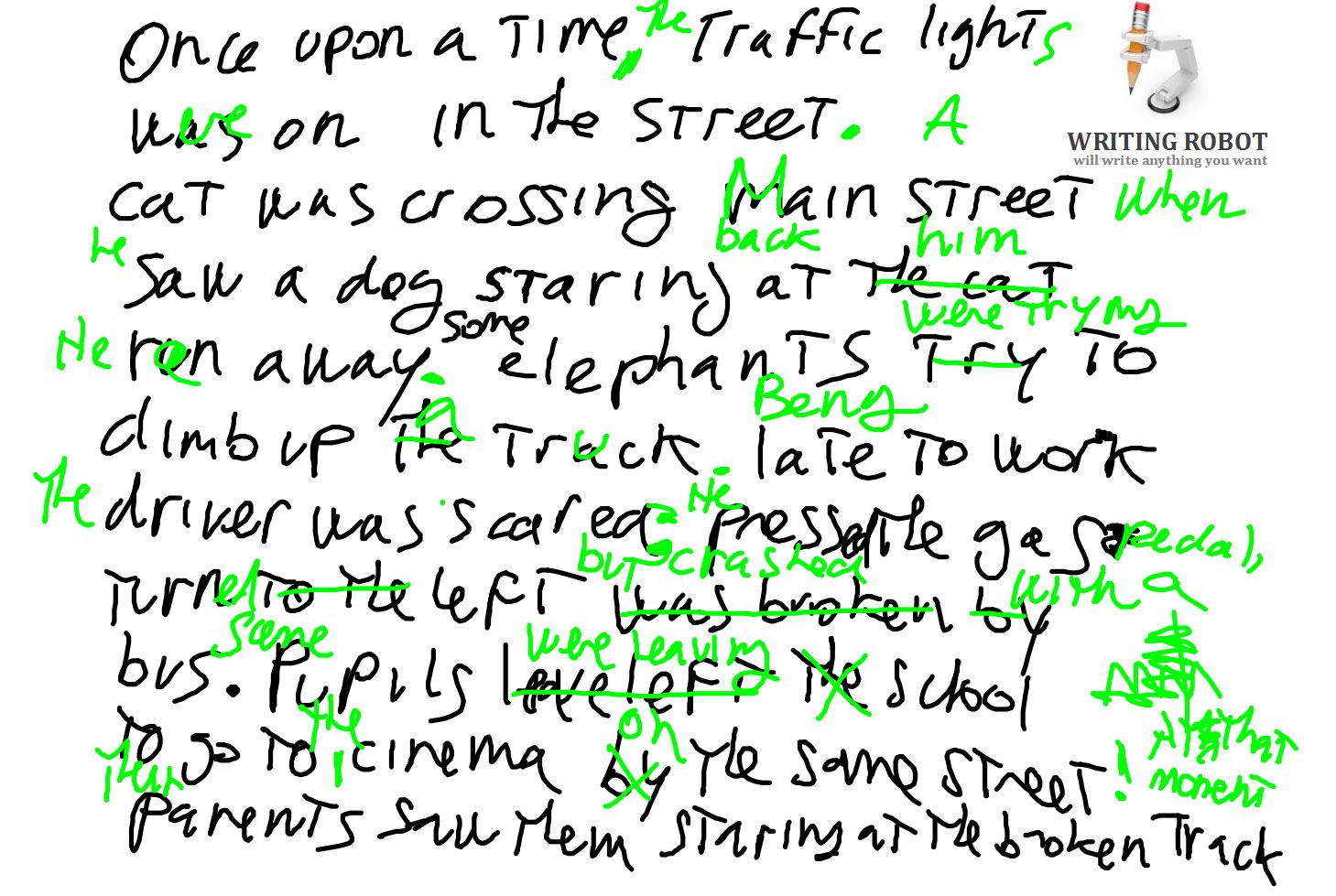

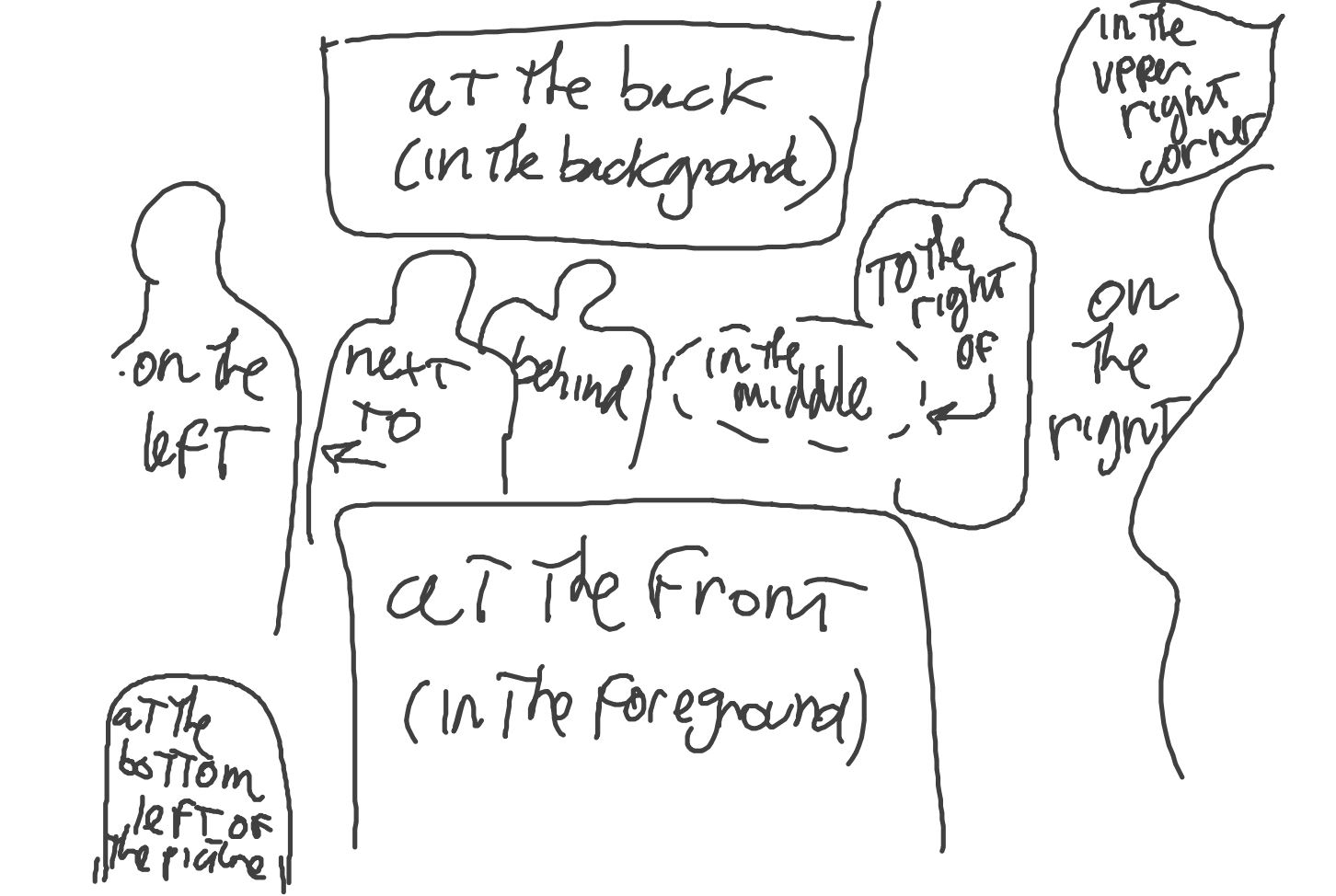

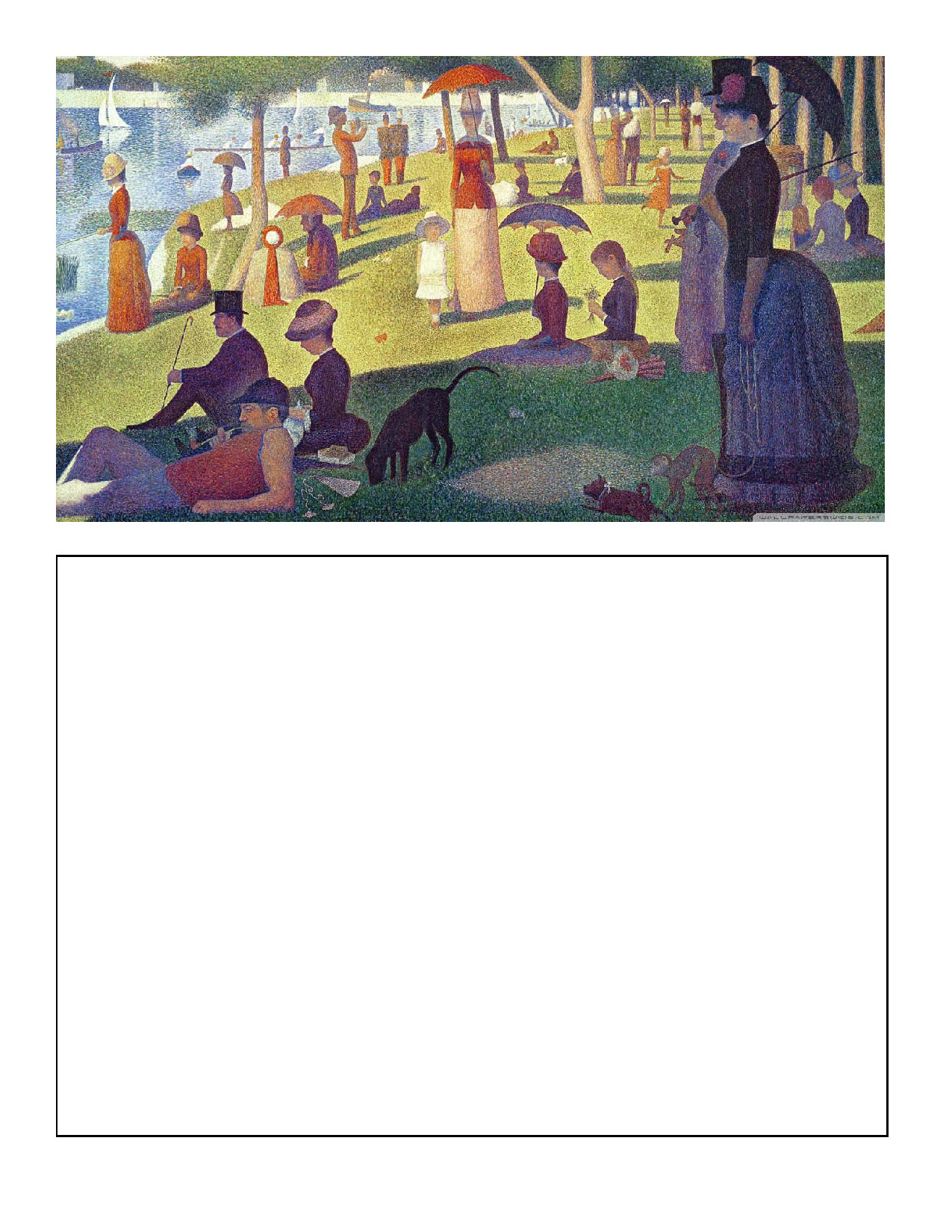

So everyday I face the tragic challenge of having to come up with an interesting lesson without using any textbooks, without diving into any of my faithful ActivInspire flipcharts, without preparing sets of images on Google, without playing videos or opening books at page x. At first I resented having to chunk my personal trove of accumulated, created and adapted material. I leave examples of one or two dogme-style classes to a following post.

.jpg)