"Please don't do your best. Trying to do your best is trying to be better than you are."

~ Keith Johnstone

I first read the name of Keith Johnstone in the very useful, quite inspiring book "Lesson from nothing" by Bruce Marsland.

I got curious about Johnston and soon bought his "Impro: Improvisation and the theatre", even though in my life I've always stayed away from stages and theaters and performances in general...

If you don't know anything about him, you can start from his recent TED apparition:

Since reading Johnstone's book, I tried to appropriate some of the games and activities it describes, especially in the part of Impro where Johnstone discusses his experience as a school teacher, before getting into theater.

Some of these became a recurrent traveling game between me and my wife, such as telling short stories together one word at a time (there's always a pigeon in there, for some reason). What's strange is that I've almost never had the courage to try any these things in class. Or, if I have, the memory of it has been quickly erased from my mind with a shudder.

I tell myself that it's hard to find that atmosphere of openness and active imagination among adults who are paying your lessons very dearly, or among kids who have been parked there by their busy parents.

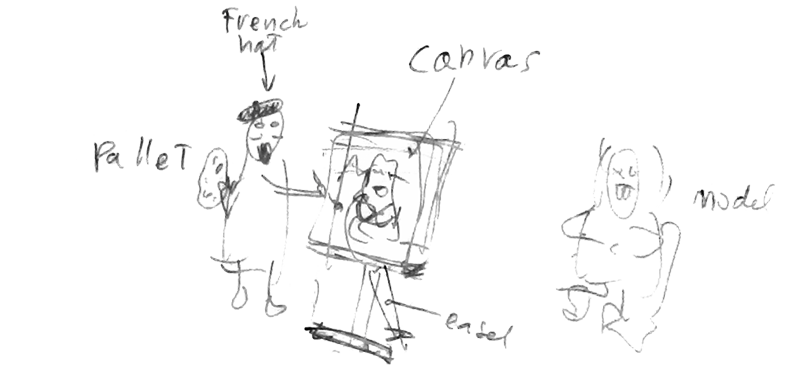

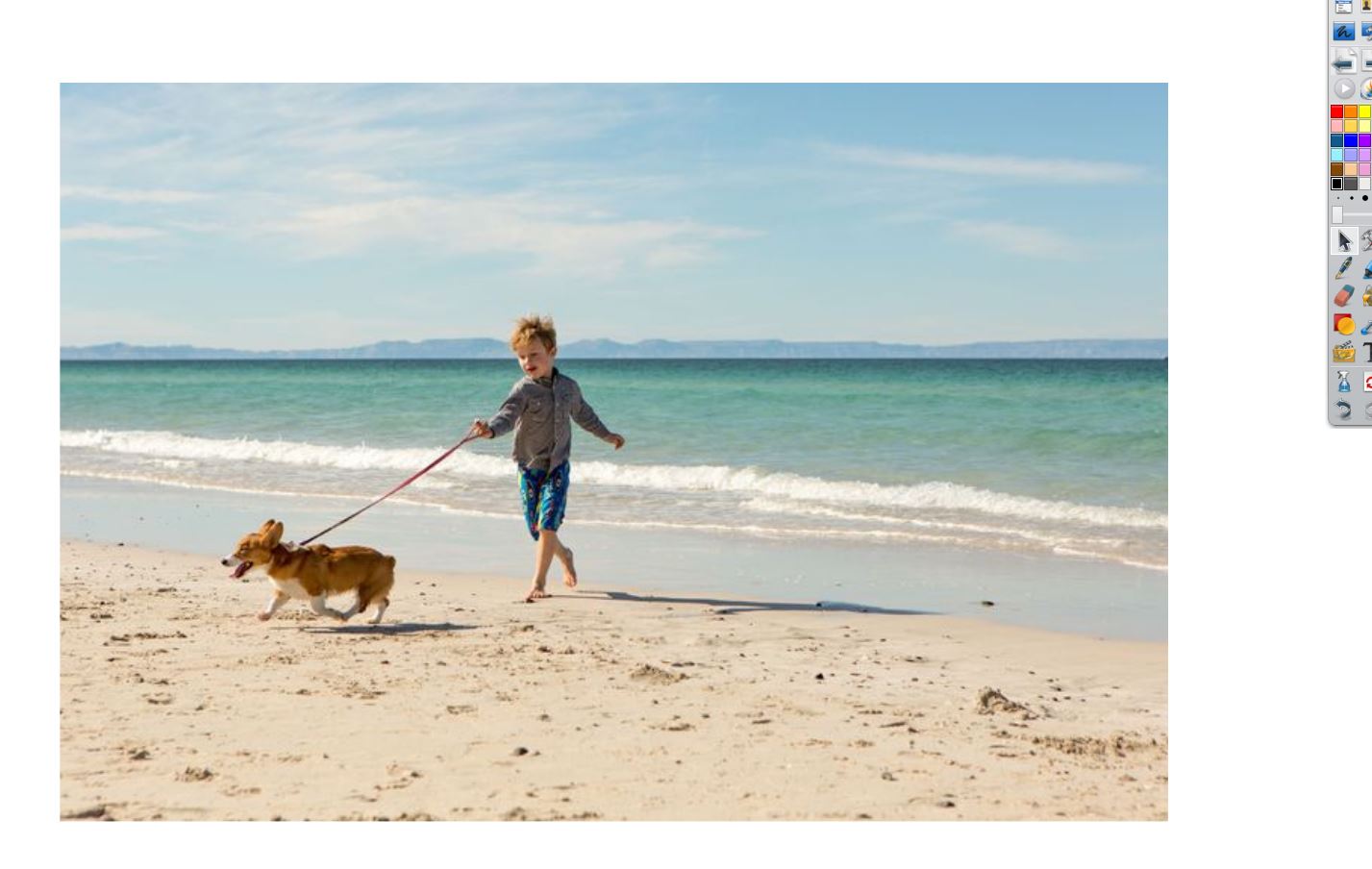

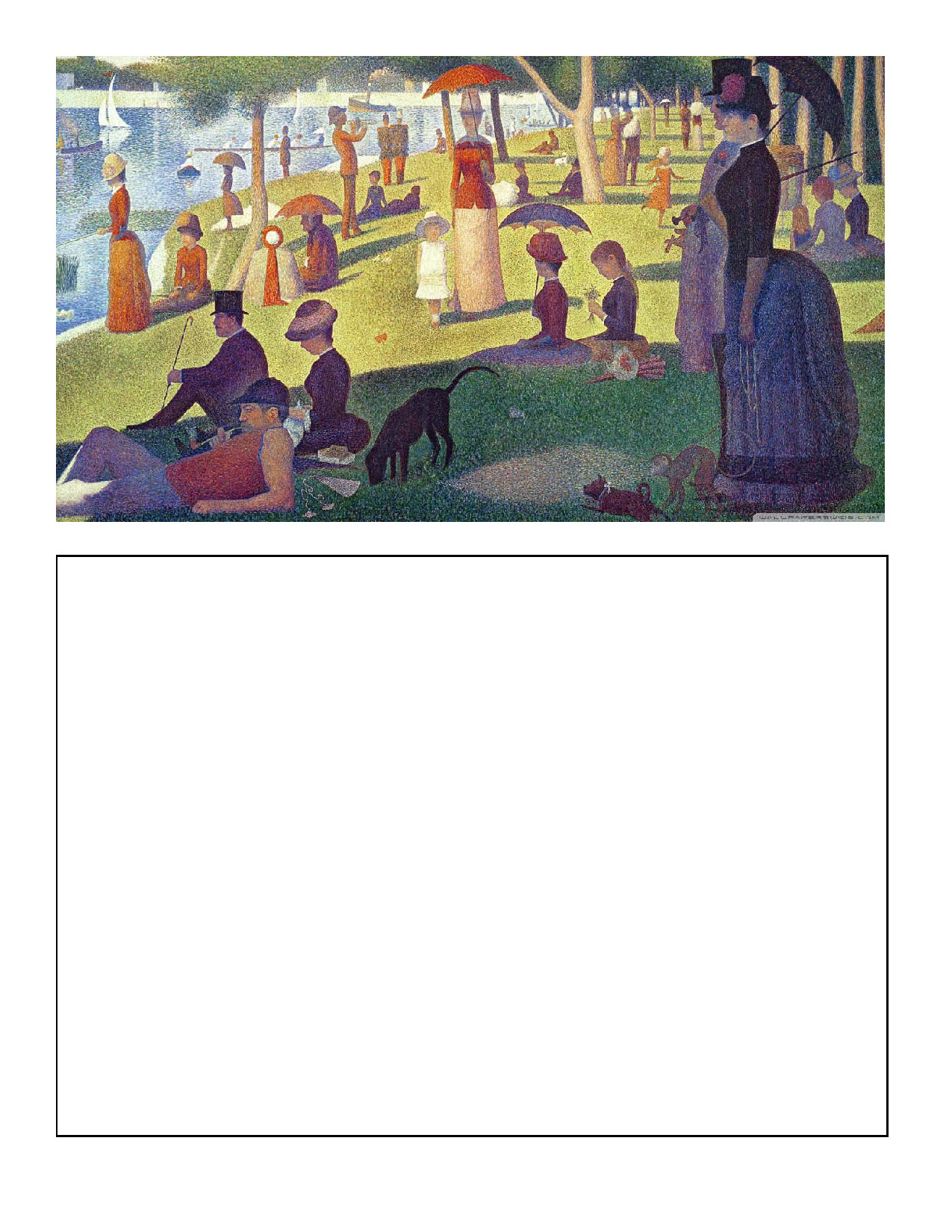

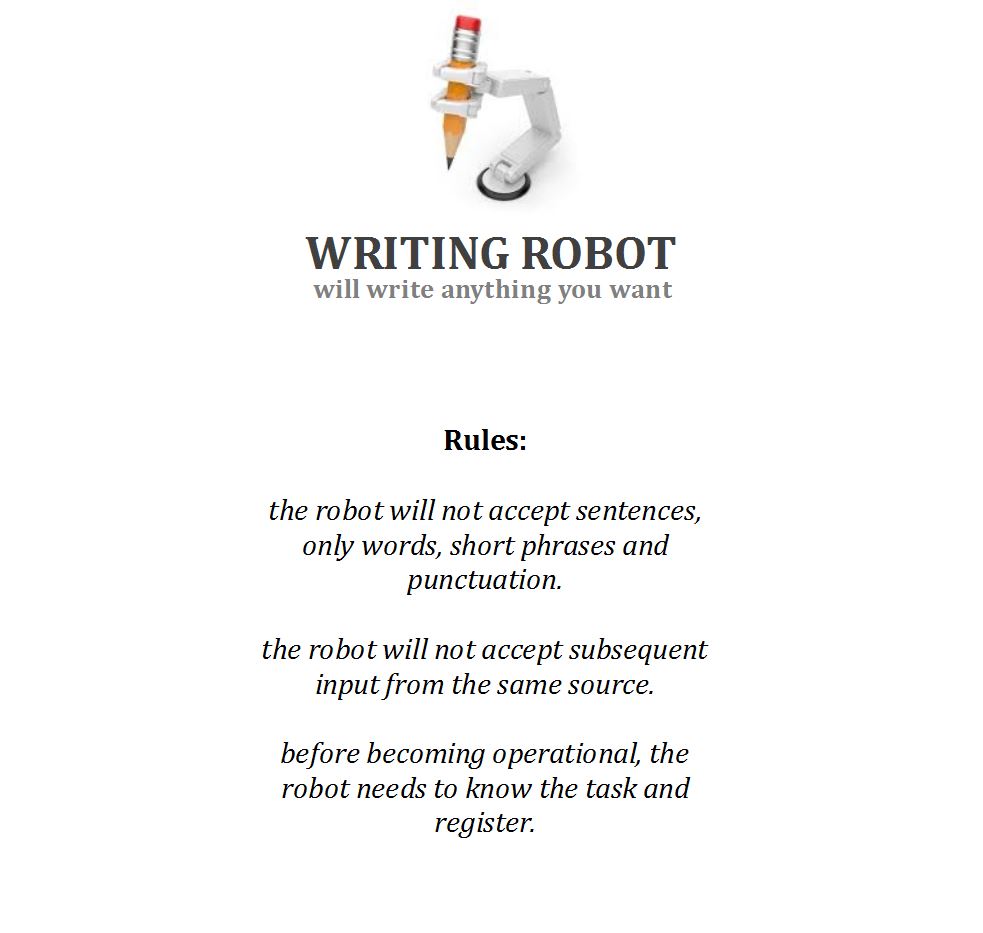

One activity I remember doing, with a beloved small class of teenagers I had for two or three semesters a couple of years ago and with whom the atmosphere was so good I probably felt I could try really new things, was "The Writing Robot". Johnstone did something like this with a typewriter he brought to class, giving his students art pictures as an inspiration.

One day I took my typewriter and my art books into the class, and said I'd type out anything they wanted to write about the pictures. As an afterthought, I said I'd also type out their dreams... I typed out everything exactly as they wrote it, including the spelling mistakes, until they caught me. Typing out spelling mistakes was a weird idea in the early fifties (and probably now)—but it worked.

Keith Johnstone, Impro

These are the first mistakes I made, because my robot wrote on the board in my ugly handwriting, and there were no pictures to take the first stories from. That's because I didn't remember that part of the book. But there's more mistakes.

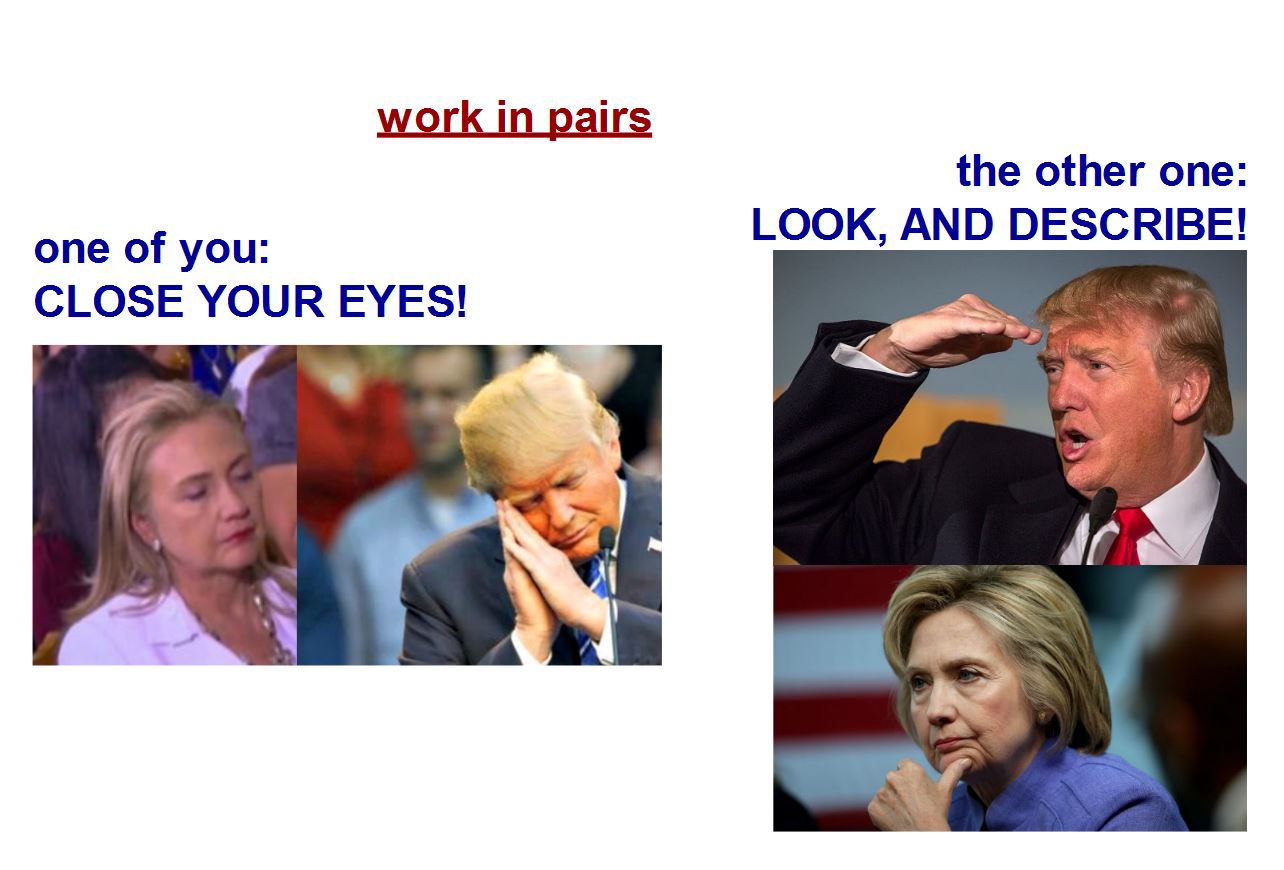

Another one was that I over-prepared for something that should have been spontaneous. Here's the first slide I presented to the class:

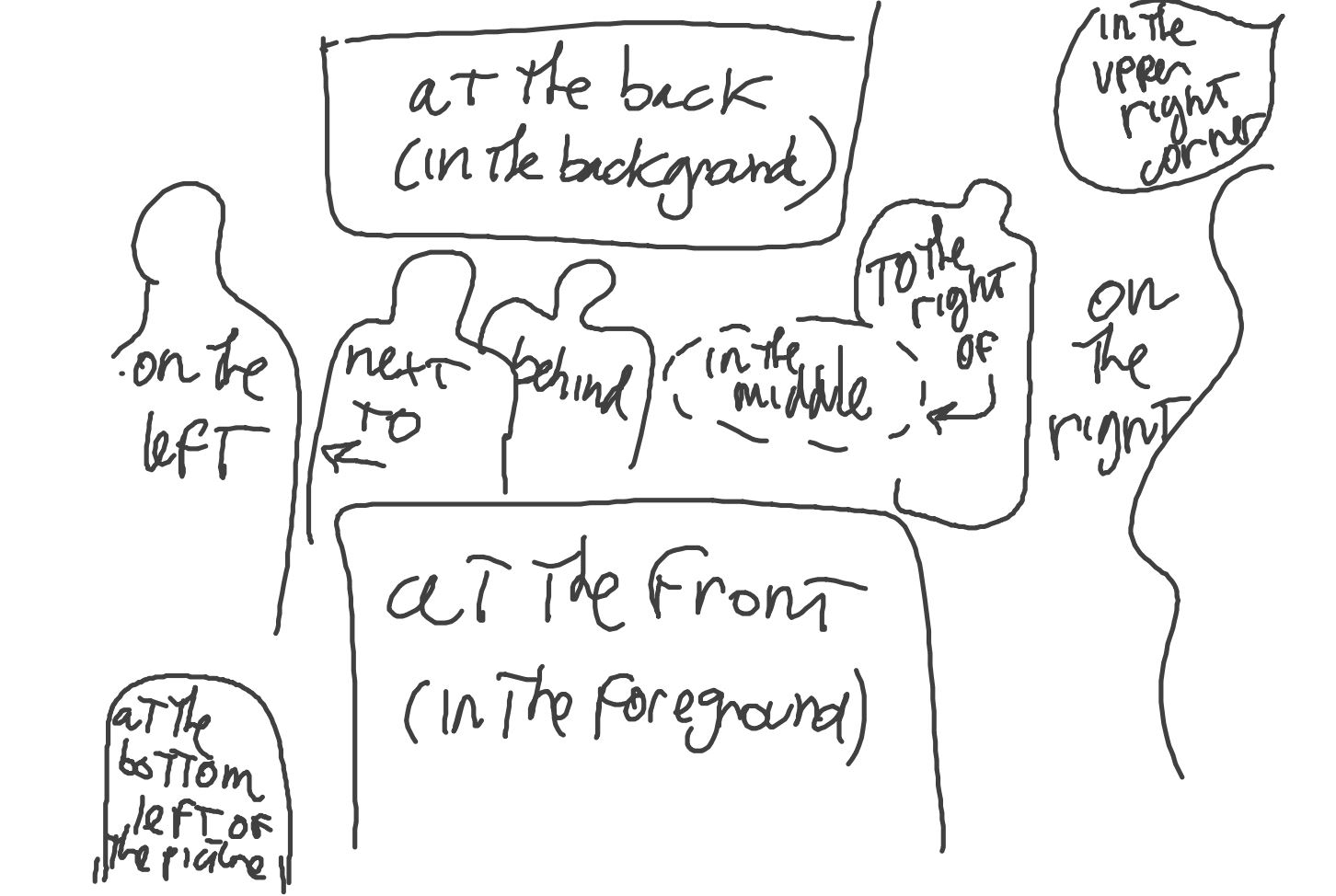

I probably thought they needed a "box". Spontaneity here is more crucial. Something like this, and the rules in particular, should have been something the students came up with. Later on. Not the teacher. There should be no official "writing robot" frame around this activity until the students call for it. This is supposed to be an illegitimate game and not a scheduled lesson stage.

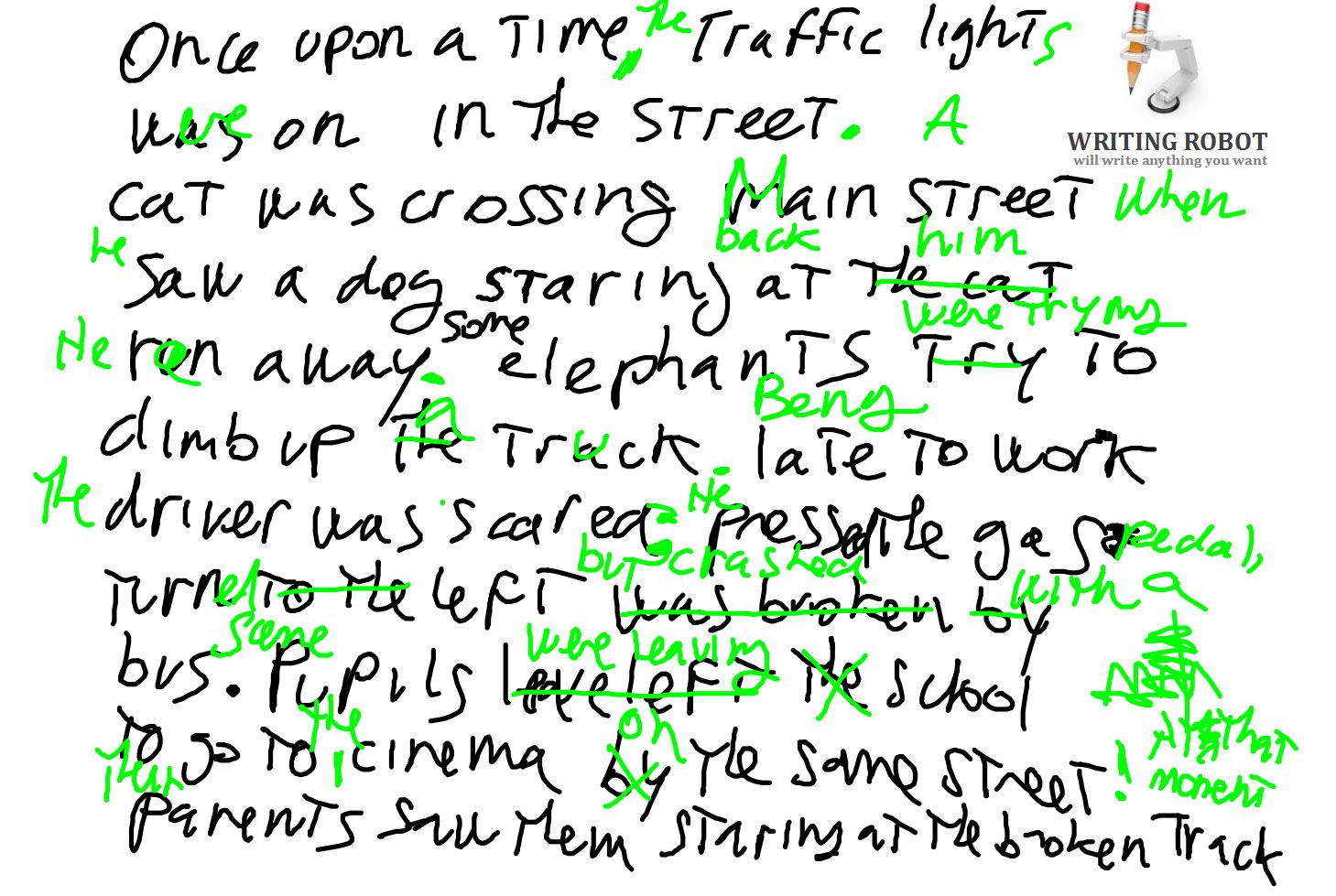

Here's the first story we wrote. I stood up next to the board behaving like a robot (lame) and faithfully printed all they suggested, going one by one:

It went on for a few pages, then we did the error correction you can see in green. The story wasn't anything special and that should have rung a bell. Instead, I thought it was smart to translate this into a classic "Delayed Error Correction" moment. Which was a mistake as well. Like Johnstone suggests, much better would have been waiting for the students to be outraged by the errors themselves, demanding corrections:

I typed out everything exactly as they wrote it, including the spelling mistakes, until they caught me. Typing out spelling mistakes was a weird idea in the early fifties (and probably now)—but it worked. The pressure to get things right was coming from the children, not the teacher. I was amazed at the intensity of feeling and outrage the children expressed, and their determination to be correct because no one would have dreamt that they cared. Even the illiterates were getting their friends to spell out every word for them.

Keith Johnstone, Impro

Until then, I should have left the activity where it was, perhaps printed and posted on a wall.

The students played the "Writing Robot" a couple of times, with all the enthusiasm and animation they were capable of. Then, incredibly, after a serious consultation among themselves, they sent forward an envoy to make it clear with me that they didn't want to play the "Writing Robot" anymore. Please.

I asked why, and they said "it wasn't that much fun", and I let it go. But immediately, instinctively, I knew what had finally spoiled this activity for them: I was too pleased with it, me and my "romantic" teaching I told all about to my colleagues as if I had discovered gold, and the students could read it.

The creative efforts of my students were going in the direction of making me feel better, and that takes only so much of our energies before we give up.

I think this, this self-pleasing teaching, this "trying for the best", in search for admiration and praise is a common problem many teachers have, because of the frustrations the job lays upon you day by day, because of the pressure we are under and the insecurities that come with it. I can only be thankful to those kids who made me see it.

So I gave up, and never thought of doing the "Writing Robot" anymore, until now... now I would do things differently, and who knows how it might go.